imperative / Java

Representation

Collected by Colleen Lewis — Own practice

Helps students plan and debug code

| PL | NM |

|---|---|

| Object | Type written and underlined in a rectangle |

| variable | variable name followed by a small box |

| int | number written in a small box |

| reference | arrow originating from a small box |

| null | X written in a small box |

| local variable | free floating |

| instance variable | shown inside an object |

The fact that each reference can only point to a single thing

Teaching students to write their own List/ListNode class

If you print/prepare these for students it is a pain, but helpful to use in class

Before students write List and ListNode classes in Java, I give students paper cut outs representing List and ListNode objects (add image). By default, the paper ListNode objects include an arrow from their variable myNext. Students can fold the bottom of one of the ListNode paper object up to cover that arrow and replace the value of myNext with an X representing null. I also give students variables such as this and current to be able to reference specific List and ListNode objects, respectively. I believe that these paper versions of the Objects are helpful for students as they plan and debug their code because they enforce the constraint that a variable can only reference one thing at a time.

Scope

The Notional Machine (NM) described here maps to the execution of Java. The NM represents local variables, String objects, objects of user-defined types, primitives, references, and null. The examples here focus on representing a linked list in Java. This NM is part of a larger NM that also includes stack frames and arrays of both primitive and object types. Neither the larger NM nor the specific NM described here include program counters, the type of a variable, class variables, or return values. The String class is the only Java library class that is included in either NM.

Mapping

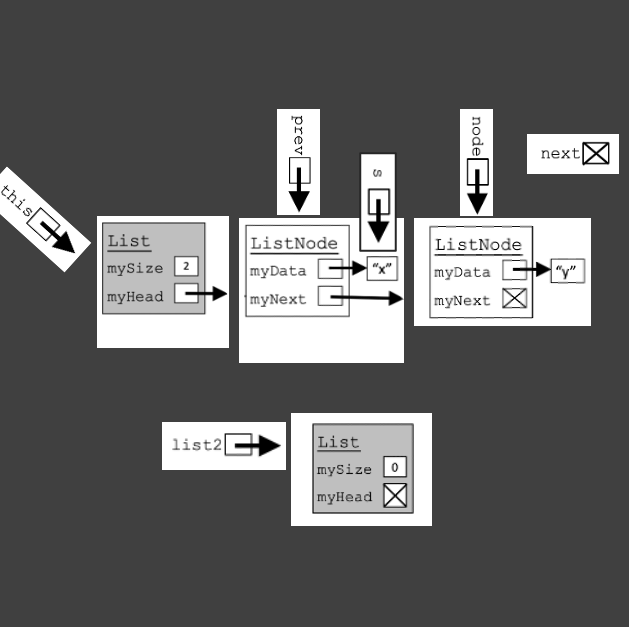

(add image) shows a List named this with two ListNodes. The corresponding Java classes are shown below. The larger NM, described above, is hand written. The NM described here uses paper representations of List and ListNodes objects. These papers are folded and written on when using them to trace through Java code.

public class List {

private int mySize;

private ListNode myHead;

private class ListNode {

private String myData;

private ListNode myNext;

}

}

I draw objects as boxes. I write the dynamic type of the object (i.e., the constructor that was called) at the top of the box and underline it. The box contains any instance variables that the object has. I shade the box for List objects, but not for ListNode objects.

I represent variables as small boxes; the type of the variable is not represented. I write the values of Java primitives directly in that small box. For example, (add image) shows the instance variable mySize, which is of type int. If a primitive value is updated, I cross out the previous value and rewrite it in the box.

To represent references, I use arrows originating from the small box. (add image) shows instance variables myHead, myData, and myNext, which are all references. (add image) also shows references that are local variables: this, list2, prev, s, node, and next. If a reference is changed, I re-position the paper so that the arrow of the newly set reference now points to the correct object. If the changed reference is an instance variable, I re-position that object and ensure that anything that was previously referencing that object still references that object. If a reference is set to null, I fold the paper to cover the box and arrow with a new box containing an X. For example, in (add image) the arrows of the local variables list2 and next are not visible because the paper has been folded back. Similarly, the bottom of the ListNode on the right of (add image) has been folded up to cover the arrow and indicate that the instance variable myNext is null.

I draw String objects as a rectangle. Inside the rectangle, I put double quotes and the content of the String. (add image) shows two String objects with content "X" and "Y", respectively. In the paper template shown in (add image), the rectangle that could include the contents of a String is empty and a String can be written in the rectangle.

Conceptual Advantages

The pre-drawn arrows on the paper mean that any variable can only reference one thing at a time. When students are tracing through code using hand-written diagrams, it can be difficult to keep track of the current value of a reference if that reference has been changed. For example, a drawing may end up with multiple arrows that are crossed out. For example, the local variable node shown in (add image) can be moved along the ListNodes to trace code that walks through the linked list. Such iteration can be quite confusing when using hand-written arrows.

In students' hand-written drawings, they sometimes draw an arrow pointing at another variable instead of having both arrows point at the same object. The paper objects seem to make this less intuitive for students and they tend to have arrows point at List and ListNode objects.

When writing code, students often make small mistakes in their code confusing List and ListNode objects. For example, students might try to access myHead on a ListNode. Coloring in the rectangle of the List objects is intended to help students recognize and remember that there are two types of objects.

Before I used the paper versions, I found that students had difficulty drawing diagrams that were helpful to them when planning or debugging their code. Each ListNode object was time consuming to draw. I used to show them how they might draw simplified versions. In these simplified versions I would write L or LN at the top of the Objects to distinguish List and ListNode objects. I would also not list any instance variables and only show the reference value (i.e., null or an arrow). These simplified versions seemed helpful to some students, but changing what a variable referenced led to crossed out arrows, which I think confused students.

In the provided classes, I append the text my to the beginning of instance variable names to try to reinforce that every object gets a copy of those instance variables. I tell students that this is why I name instance variables in this way.

Conceptual Disadvantages

The way String objects are drawn is not consistent with Objects of user-defined classes. My students have never commented on this inconsistency, which might be because I use String objects in these diagrams before I introduce objects of user-defined classes.

What failed attempts have you had? I tried prototyping versions that used ribbon or yarn for the arrow. However, this made working with the pieces too cumbersome and did not seem to add functionality.

I made a version of these for the Binary Search Tree (BST) class. However, I found it easier to draw pictures of the trees because the changes to the BST structure were typically just changes of a single reference and the rest of the structure of the BST needed to stay unchanged. Unfortunately, arranging the papers in the BST structure was cumbersome and easily disrupted.

Introducing the NM to Students

Instructional Context

In my CS2 course, my students are learning Java. I have them implement a linked list structure in Java to help them practice with Java references. This is students' third, week-long assignment using user-defined Java classes. I use a ListNode class nested within the List class as shown in (add image).

I start using similar drawings when I introduce arrays (before I introduce Objects) and students practice creating these drawings during lecture.

Depending upon the term, my lecture sessions have 50 to 150 students. Students are accustomed to working in pairs to write, trace, or discuss code throughout a single lecture. During a typical lecture, students are asked to work in pairs between 5 and 10 times. My lecture period is 75 minutes and the following instructional sequence might take between 30 and 60 minutes.

Instructional Sequence

I give students a set of these papers at the beginning of class. This involves copying and cutting a set of these for each student, which is a pain! As a review of Objects, I ask students to write the Java classes (and instance variables) that they can infer exist. They haven't seen inner classes, but hopefully find this task not too difficult. Under a document camera, I show them that you can fold the bottoms up. After going over the resulting Java classes and introducing inner classes, I ask students to write a constructor for each class. I go over the constructors and then ask students to draw a memory model for the code shown in (add image). I use this to help students see that the variable spam1 references an empty List and the variable spam2 is null. The variable spam2 is a variable that \textit{could reference a List object, but it does not.

public static void main(String[] args){

List spam1 = new List();

List spam2;

}

Next, students write code for a method addToFront(String s), which is shown in (add image). To try to make the task easier, I tell students that this requires only four steps. I encourage students to figure out the steps on the paper Objects with a buddy before trying to write the code. Before I used these paper cut outs, few students were able to complete the task. Now, after most pairs of students have a solution, I go over the answer. I illustrate the steps under a document camera with the paper objects a few times before showing how each step translates into a line of Java code. To remind them that we always need to consider the case of an empty List, I ask them to discuss with their buddy if this would work if the List was originally empty; it does. Throughout my course, I always use the variable this explicitly because I want to draw students' attention to the fact that those variables are instance variables and not local variables.

public void addToFront(String s){

ListNode node = new ListNode(s);

node.myNext = this.myHead;

this.myHead = node;

this.mySize++;

}

Next, I ask students to trace a version of the method, now named addToFrontWrong shown in (add image). In addToFrontWrong, I flipped the order of two lines of code from the correct addToFront method. The line this.myHead = node; results in losing ListNode objects that were in the List before the method call. The line node.myNext = this.myHead; results in the instance variable myNext in our newly created ListNode to reference itself. I point out that as a programmer we sometimes feel really frustrated when we find that we only needed to make a tiny change in our code to go from broken to working coding. I explain that we just traced a tiny change that made everything break! The details matter and we need to be paying attention to what our code does step by step. I also point out that we could have written the line this.mySize++; anywhere in the method.

public void addToFrontWrong(String s){

ListNode node = new ListNode(s);

this.myHead = node;

node.myNext = this.myHead;

this.mySize++;

}

public int length(){

int count = 0;

ListNode node = this.myHead;

while (node != null){

node = node.myNext;

count++;

}

return count;

}

Last, I have students write code that counts the ListNode objects in the List, and I acknowledge that it is a pretty silly task because the List class already has an instance variable mySize. I use length as shown in (add image) to introduce how we walk down the elements in a List. Again, I show the steps on a sample List under a document camera before translating the steps to lines of code. I point out that the variable node is a local variable and changing it does not change the structure of the List. I explain that because students will often modify a local variable when trying to modify the underlying structure of the List, but I don't know that my pointing it out leads to any fewer occurrences of the error.

Do you have feedback on this notional machine? Did you find a mistake, or do you have a request for improvement? You can create an Issue on GitHub, where the description is hosted. This way we can see your feedback and address it.

For this, you need a GitHub account. Then follow this link to see the source file of this page. In there, click the ... left of the highlighted line, then pick "Reference in a new issue".